I wanted to be a star, not a gallery mascot.

—Jean-Michel Basquiat

1.

I arrived a little after 9:30, under a brilliant East Village sun, to a line, or what would become a line, out front of the Brant Foundation Art Study Center’s 6th Avenue building. I was the lone negro in line, and would remain so, even as the line grew, minute by minute, with others who’d taken the Foundation up on its late offer to extend waitlist tickets to its gold mine of a show—a solo exhibition of paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat.

You’re reading this, so chances are you’re at least passingly familiar with the work of Basquiat, as his influence on the style and culture of my generation and the one immediately preceding it (and perhaps those that follow, to an even greater extent) has been massive. A black kid from Brooklyn with a father from Haiti and an American mother of Puerto Rican descent who became the darling of the Lower East Side art world for a few years in the 80s before passing, in 1986, of a drug overdose, Jean Michel Basquiat is and was, to put it plainly, significant. He was only 27 when he died, and was posthumously included, once white youth culture found out about him (and admitted into its ranks enough black youth culture), in the “27 Club,” a cultural list of influential artists who died at the age of 27, a list which includes Amy Winehouse, Kurt Cobain, Janis Joplin, and Jimi Hendrix, to name a few.

His contemporary value as an icon of 80s LES cool culture resonates in the prices his work demands, most notably his 1982 “Untitled,” which sold for $110.5 million in 2017. His influence can be found in more places than can easily be enumerated, from the proliferate saturation of styles mimicking his boldly-colored, quickly-executed, encyclopedic compositions, to the way he wore his hair, carried his body, his understated brilliance that warped the reading primarily white spaces were inclined to impose on said body, turning its historic danger into the danger of knowing too much too deeply. He was mysterious and inviting, playful and morose—and a genius, whatever it means. We know what it means, or at least how it feels. He was hip-hop. You can feel him in the Kid Cudis, Donald Glovers, LaKeith Stanfields, as much as in the Rashid Johnsons, Nina Chanel Abneys, and Derrick Adamses. He is, for these and so many other reasons, one to whom a generation-plus of black, strange, artsy kids have aspired.

2.

I arrived early. And I stood in line until my friend D got there to join me. By that time, other folks of color had joined the line, which had grown large enough that passerby stopped their morning strolls through the posh neighborhood to ask what we all were waiting for. “An art show,” I told one or two of them. “Jean-Michel Basquiat.” That was enough to elicit some semi-familiar (if self-conscious) smiles and some expressions of joy that this building was being put to good use, apparently for a cause interesting enough that such a queue would form for it.

Finally it was our time to go in, and, after being beckoned, D and I entered. We were to go to the top floor on the elevator and experience the show on each subsequent floor down.

3.

In the ceiling of the top floor is a skylight pooled with water. Morning shone through it, casting a dazzling liquid light on Untitled (1981). The brightness of this light, that it moved as it did, mesmerized me, and for a long time I stood before the painting, which I’d seen so many times in books, documentaries, on social media accounts, on merchandise, but never so spectrally. It struck me then as profoundly true that the second best way to experience a painting is to stand in its physical presence and let whatever ineffable qualities be consumed in the subatomic spiritual exchange between you and the work (the best way, of course, is to paint it yourself). I took my time with each of the dozen or so large works in that room, feeling suddenly that I was being afforded an opportunity I shouldn’t squander with inattentiveness. Nonetheless, I took out my phone and made photographs.

Passing through the space, I saw a black security guard standing, quite literally, in a shadow. I approached him and asked if he was familiar with the artist. “I just got the call to come in this morning,” he told me. Breathlessly, perhaps on the verge of mania, I told him what I knew of Basquiat’s story, where he was born, where he lived, what preoccupied him. I told the security guard, “This work is for us. Even though there’s not much of us in here,” hoping he’d understand that by us I meant what FUBU meant, black folks. I could tell he heard me, but also that he was there to do his job, not to look at the paintings, and whatever value the experience of standing in front of a painting might hold, he couldn’t at the moment do it because he had to stand where he was standing and watch all of us watch the paintings. Not a full hour later, as I stood on a lower floor, I saw him walking toward the exit.

4.

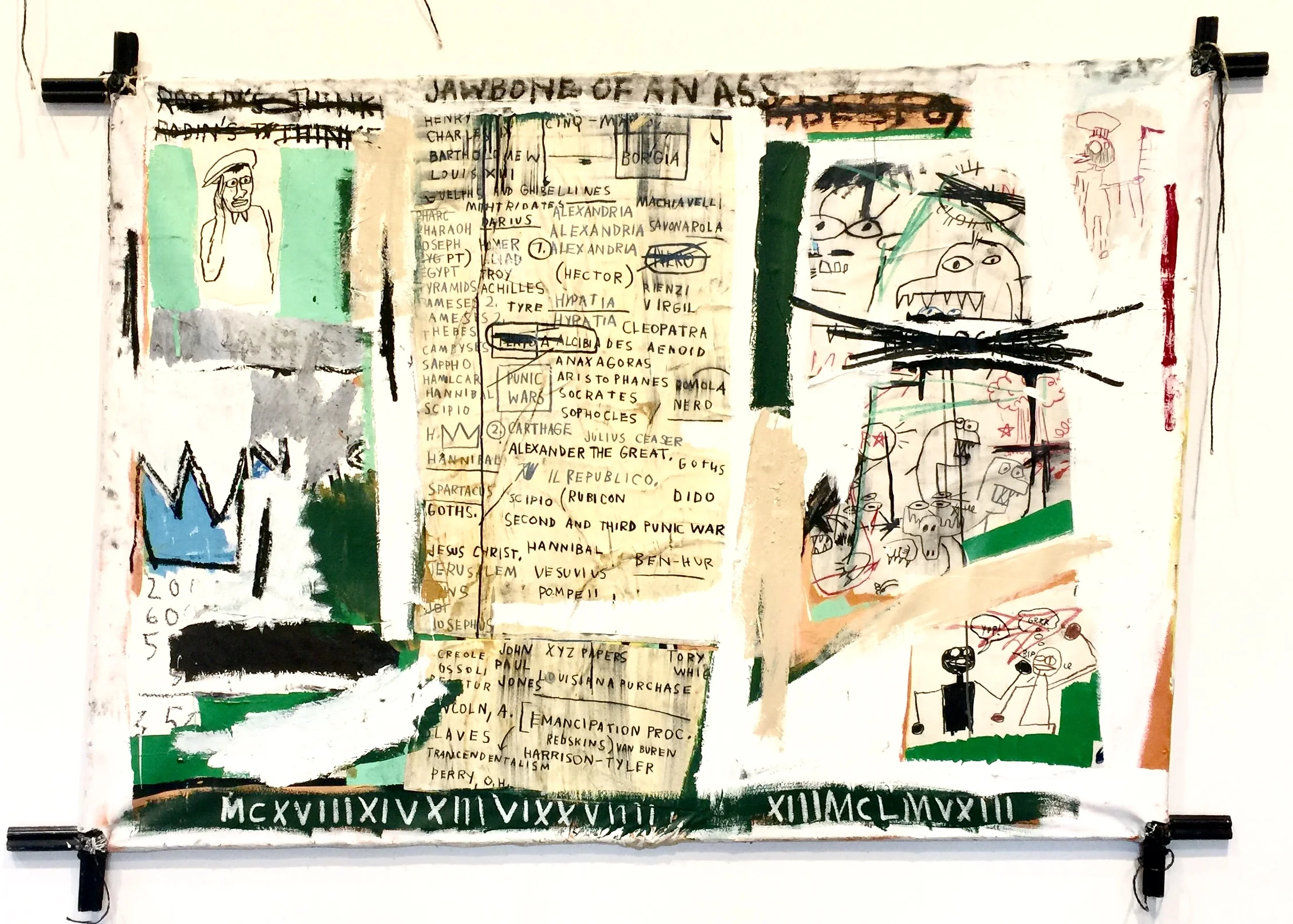

Jean-Michel Basquiat executes spatially as a preadolescent notebook doodler might, obsessing in arranged fragments, the hand-drawn collage. His aesthetic prefigures the manner in which hyperspace arranges ideas in the organism known as a human mind—a phenomenon he captures in the phrase “Boom For Real,” as his friend, fellow street artist Al Diaz, explains in The Radiant Child documentary (the phrase also titles another recent documentary, directed by Sara Driver, about Basquiat’s late teenage years). The explosion of reference points on his canvases brings to mind the explosion of reference points in virtual space. The references can easily appear to be so varied as to almost be random, haphazard, chaotic, lacking order. But I think they’re precise: he was thinking differently before the world forced us all to think differently, speaking to the formulation of ideas in a manner—not ahead of his time, but way up in the middle of his time, deep enough in the middle of it to feel where it was going, like one who can read the type of tree by how the soil bulges just before its first sprouts breach the surface. His paintings exhilarate in their enumeration of signs, and the speed at which they’re executed (for it’s clear, when you’re standing right up next to one, how fast he painted) brings to mind the work of a clairvoyant or a mystic, a person working as a conduit for a force more certain than they could be about the way of things.

Spatial execution like a child: that’s why his art was in the 80s, and to this day by many is still, described as naive, or primitive. There’s a sense in his paintings and drawings that the intelligence that composes these works differs from the standard, savvy, adult, refined ones that make, for instance, hyperreal or geometrical or even cartoonish paintings; they differ, furthermore, from abstraction proper in that their points of reference are a step more adherent to available signs than, say, Cy Twombly’s scribblish works, which Basquiat so deeply admired. No, Jean-Michel’s works indulge in bold regions of color against other bold regions of color, brilliant gestures that act both as erasure and as mark-making, evoking the street walls where advertising posters have been layered, torn away, pasted and tagged over, and grown old. There is a sense, then, not only of the collage but of the palimpsest, nature’s primordial collage. That they are made with oil stick and acrylic only further gestures to their mnemonic function—this is what I was thinking as I stood before that top level of work, which consisted mostly of portraitures, meditations on black prophetic and reflective figures clearly drawn from (and participating in) a tradition practiced by indigenous peoples the world over.

5.

An indigenous practice, or one that looked indigenous, that included points of reference valued by the orthodox centers of the west alongside those discredited points of reference the west sought to colonize out of their potency, practiced by a handsome, strange, ambiguous, young black artist who lived on the streets, must have been irresistible to the Lower East Side elite, who, like the settler elite in all other first-world locales, require the raw materials of marginalized culture to consume. Here before them stood a young negro boy, gifted with curious ideas, multiple languages, a penchant for what their episteme still categorized as native sensibilities, who was willing, by all accounts, to deejay their parties, to dance, be shown off, spoken to, copulated with.

“I may even be said to possess a mind,” Ellison’s unnamed narrator says in the Prologue to Invisible Man. It was like this: the manner in which Basquiat grew from boy to phenomenon was the equivocal hearsay of the possibility that the savage possesses, that what the savage possesses can be called a mind. How thrilling it must have been to be one of them, moving before these massive works, to say with your whole chest that this is High Art because you say so. To think of how much money it could make. A cash cow, this young man, sick with the very codes by which he’s judged, these works a conjuring against it—a work horse.

6.

It was my first time being in a space with so much of Basquiat’s work. I’d aspired to it for so long. Imagined myself getting nearer and nearer the man through his hand, through how his hand told of his mind. I expected that upon nearing him the right way I’d begin to understand why his works make me and so many others feel less alone in the world. As I walked among them, I do believe I approached that understanding; I knew, at least, that I’d have to write about him, that so much of what I’d already written was about him without my consciously knowing it.

7.

On the third level, D made a friend: a chef-artist who noticed that as she stood before the works, D didn’t take out her cell phone like the rest of the gawkers in the room. This told her that D was someone who really wanted to take in the presence of the work and not (the suggestion may be drawn) merely to share images of it on social media. When D told me this, I smiled. Her friend was absolutely right. I felt the beginnings of a twinge of shame arising in me, dissipating in the heat of my jacket. It passed. I remembered why I was there and why I had my phone out, like a tourist at the pyramids, capturing every angle of these works. Maybe tourist is unfair; the better word is pilgrim. I didn’t put my phone away because I was ready to admit that I was in a place I found holy, even though I had never composed an argument for its holiness, at least not an easily legible one.

So let me start that now.

note: corrected an earlier version’s misnaming the Brant Foundation Art Study Center and corrected Basquiat’s mother’s country of origin from Puerto Rico to American of Puerto Rican descent.